I recently came across an excellent lecture given by Dan Ariely at Google. His topic was behavioral economics and the ways in which human decisions are influenced by outside conditions. Of particular interest is a part of the discussion that deals with cheating behavior and the use of tokens. For proper context, I recommend watching the entire lecture but the truly relevant part begins at about 41:56 (see quotation below).

Authors@Google: Dan Ariely

According to Dan’s research, humans are less likely to cheat with money directly than they are to cheat with things once or twice removed from money. When students were given the opportunity to lie about an amount of earned tokens instead of money, the degree of cheating doubled.

In Dan’s own words:

For me this is perhaps the most worrisome experiment of all we got because we are moving to be an economy that is not about money; it is about things that are at least one step removed from money. Think about a CEO who is back-dating their stock options. It’s not money, it’s stocks; it’s not stock, it’s stock options. It’s not asking for more, it’s just changing the date a little. Could it be that somebody who would never imagine stealing $100.00 from a petty-cash box could nevertheless very easily back-date their stock options and still feel honest about their overall behavior. I think the answer is absolutely yes. Could it be that when people cheat on Paypal and other things that are a step removed from money (credit-cards) it is actually easier for them to be (to feel) honest and at the same time cheating.

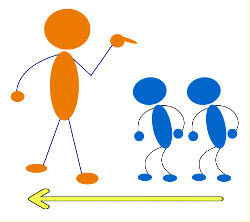

So what happens when we take a step away from money but in the other direction. Rather than abstracting money to something else, like tokens or stocks, what if we test the human willingness to cheat with respect to something of immediate value rather than after it has already been abstracted into money?

Dan said that stealing is more common when we take a step away from money and his examples only are in the direction of more, rather than less, abstract forms of value. But how would the likelihood of cheating change if we went from money to something more immediately valuable? Would we experience an increase in cheating, just as when going beyond money, or would be find that cheating was actually less? Would we find that money is itself one step removed from real human value?

Dan is a scientist and clearly states that we need to do experiments to determine these sorts of behaviors. They can not be intuited. Someone needs to initiate a comparable experiment where actual value was one of the experimental controls. Could we imagine an experiment similar to the test-taking scenarios that Dan outlined, but in which payment was not in the form of money, but rather in something of intrinsic value to humans – candy perhaps? Is the Coke experiment already an answer to this question?

The real question here is whether the use of money as an abstraction of value has already created a tendency for humans to cheat – a tendency that might be repaired somewhat by a civilitic model in which people’s rewards are more closely tied to the more-real value (the contribution) of their actions.