Once upon a time, in a land not too different from our own, there were two political parties. For the sake of distinction, we might call them Posicans and Negicrats. In principle, both parties wanted the same thing for their people: freedom, prosperity, education, health, safety, and so on.

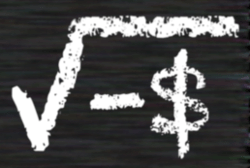

Imagine: complex economics

Unfortunately, the politicians were divided on one particular point, which caused them to support contradictory solutions for their economic problems: The Posicans, it turns out, insisted the square root of one dollar (?$1.00) is one dollar ($1.00). Meanwhile, the Negicrats believed the square root of one dollar (?$1.00) is actually negative one dollar (-$1.00). Both sides could make reasonable arguments for their assertion, suggesting that their opponents were wrong. Moreover, neither side could account for the square root of negative one dollar (?-$1.00) and accused anyone who considered such a complex thing of imaginary thinking.

Ultimately, the people were completely divided and their land was cast into a long and bitter conflict. Neither side was willing to believe the other could be correct and imagined their foes were solely interested in personal gain. As the debate continued over many years, it became obvious that members of the opposing viewpoint were corrupt.

It was not apparent to anyone that both sides of the ideological divide were correct, just as much as they were both wrong. Both Posican and Negicrat economics provided only simple and incomplete solutions to a more complex problem. When a theory of complex economics, and the tools to support it, was ultimately proposed, it consistently accounted for all of the Posican ideals as well as all of the Negicrat ideals at the same time.

However, locked into their narrow view that the truth could be only one way or the other, neither Posicans nor Negicrats could believe their economic model was a restrictive one. They would not consider that their society might be able to have it both ways where everyone could prosper.

Ultimately, unable to challenge their basic paradigm, the conflict continued, the world burned, and all was lost.

Civilitics: a complex solution to simple economics; not so easy to understand, but worth the effort.