Thomas Carlyle referred to economics as a dismal science in his work, Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question, published in 1849 because he believed the new science of economics, with its market forces of supply and demand, would undermine the social advances that had been achieved through slavery. Consequently, he argued, any cultural shift from slavery to exchange economics was doomed to a dismal future.

Slavery

Of course, time has shown that exchange economics ultimately brought about great industry and advances in science and technology. So we might conclude that Carlyle was mistaken and economists can wear the dismal badge with pride in the sense that it successfully replaced the ethically-corrupt institution of slavery while being at least as productive. In her TEDx presentation, Jodi Beggs remarked, “If that’s what we are going to consider dismal… Hey, sign me up!”

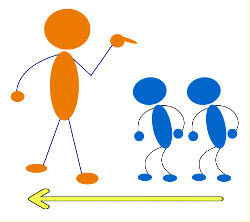

If we look at the production of value as we progressed from slavery to exchange economics, it might look something like the first two diagrams at the right. The first diagram characterizes slavery in the sense that an entity (large orange figure) exercises relatively complete power over one or more individuals in an unequal relationship. In this arrangement, the master exerts power over the slaves and wields coercive power over them, which is used to transfer value from the slaves to the master (yellow arrow). The slaves, who are powerless in the relationship are also the ones who provide most of the productive value in the relationship.

Exchange economics

In an exchange economy, the power appears to be more equally shared between participants. While the power sharing may not be totally equal, we could characterize an economic relationship as one in which both parties wield some degree of power over the production and transfer of value. In a market, for example, the seller has control over the price of goods and the buyer has control over whether or not to buy those goods. Of course, this is the system most prevalent in the modern world, and the one that Carlyle predicted would be a dismal failure.

Unfortunately, the situation under exchange economics is often much closer to slavery than we are led to believe. Employers sometimes wield unequal power over their employees because the employees are dependent upon their jobs for survival. This form of economic slavery can be seen in sweat-shops in the developing third-world as well as in certain jobs within industrialized western nations. Indeed, it is remains a fairly dismal outcome of the economic model.

Normally the economic discussion stops there and does not consider anything else. After all, what could be more progressed than exchange economics? Slightly dismal though it may be, it is certainly better than the alternative: slavery.

Civilitics

At this point, I direct your attention to the third graphic. In this case, the graphic is much the same as the first (slavery) except that the arrow now points in the other direction. From that point alone, we might want to conclude one of two things: Either (A) it is very similar to slavery and just as bad since the power is unequally held, or (B) it might actually lie at the other end of the spectrum, being as much better than economics as economics is to slavery.

My intention is to show how civilitics, represented by the third diagram, is ethically more sound than exchange economics. In fact, I would like to recast exchange economics as the dismal science it has turned out to be.

Whereas civilitics depends on a similar disparity of power as slavery, it does so by inverting the power structure, making the power holder the one who transfers value to those without power in the relationship. The immediate question one might ask is, “What would prompt someone with power to voluntarily give away value to those who have no power?”

The answer to that question is inherent in the nature of a civilitic system. In simplest form, it is the giving away of value that entitles one to receive additional value from others as part of a slightly altered social contract. This is not so different from exchange economics in which one must make money in order to have the money to spend. Said differently, one must initially provide goods or services in order to eventually buy goods and services.

The significant difference is that civilitics is not based upon reciprocity (exchange) between individuals, but rather upon one’s participation to the public benefit as a whole. Because value is strictly given (as a gift), and the benefit to the self is decoupled from the giving relationship, the tone of every transaction is shifted from “What’s in it for me?” to “How can I help?” This is a subtle but very important difference.

Ultimately, economics has given us many great wonders. But it has also nearly about broken our planet. Without economics, the infrastructure that will build civilitics could never be built. So it’s a mixed blessing. Maybe dismal or maybe not. Either way, it is time to move forward, just as we once moved forward away from slavery.